THE "SCIENTIFIC" JUSTIFICATION FOR URINE DRUG TESTING

John Morgan, Medical professor and acting Chairman of Pharmacology, City

University of New York Medical School

KANSAS LAW REVIEW, 1988, Vol. 36, pp. 683-697

INTRODUCTION

Just as drug use is often ceremonial and ritualistic, discussions

about those problems have a communal, worshipful character. Individuals

have to speak out of strong conviction, and congregational beliefs are

strengthened in a confirmation of faith and shared attitudes. In recent

years, the experiences described above have been characterized by an

important cohesive element, a shared litany.

Since 1984, when urine testing of unimpaired civilian workers began

to expand rapidly, its public supporters have used a common set of

statements, ideas, and statistics to justify the imposition of the forced

detection and testing of urine for illegal drugs. The use of this

religious language is not without a purpose. Litany is seldom questioned,

nor is the speaker of litany often called upon to prove the truth of his

statements, even when they involve things material and not spiritual. I

believe this common set of statements used by those justifying and selling

urine tests is repeated, polished, and accepted with a minimal offering

of

proof. In this article, I will identify these statements, search for their

sources, and examine their accuracy.

II. THE FIRESTONE "STUDY"

Obviously, statements concerning the job performance of drug users

have an impact on their employers. From the earliest days of the debate,

a

series of statistics about drug-using workers, their poor productivity,

and

high cost to ther company have been presented.

In one of the first proceedings of a meeting directed to the issues

of drug abuse in the workplace, Robert Angarola and Judith Brunton stated:

A recent study....suggests that drug users were almost four times

as likely to be involved in a plant accident and were two and one-half

times as likely to be absent from work for more than a week than employees

who did not use drugs. Drug users were five times as likely to file

workers' compensation claims and they received three times the average

level of sick benefits. (1)

Further, the drug users were "repeatedly involved in grievance procedures."

The Angarola-Brunton document was published in 1984 but they and others

had begun making the remarks frequently by then

In 1987 testimony before the U.S. House of Representatives, by

Mark de Bernardo of the United States Chamber of Commerce:

'recreational' drug users are---

--2.2 times more likely to request early dismissal or time off...

--3.6 times more likely to injure themselves or another person in a

workplace accident.....

--5.0 times more likely to file a worker's compensation claim. (3)

For at least five years, these statistics and others like them have

been voiced and published by testing advocates, although seldom with de

Bernardo's decimal-point precision. Those whom I have quoted seem to be

referring to any user of illegal drugs and de Bernardo specifically speaks

of recreational drug user. Yet, one might wonder how these data were

gathered, particularly since drug testing in the workplace is proposed to

uncover the secret user. How were these users described by Angarola and

de

Bernardo (and many others) found and analyzed? The answer, as is often the

case is simple. They were not.

The most important source for dissemination of these statistics

seems to be the Drug Abuse and Alcoholism Newsletter of Dr. Sidney Cohen.

(4) This monthly newsletter is widely distributed and has been collected

and published. In the August 1983 newsletter, Cohen discussed a study by

the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company and constructed the quotable

statements which have appeared and reappeared: "Drug users were five

times

as likely to file a Workers' Compensation claim, and they received three

times the average level of sick benefits." (5)

The Firestone "Study" has never been published. Thus, Cohen's

newsletter seems to be the source of all such statements. Yet, Cohen

gave no attribution nor sources, and when I wrote to him in 1985 he

answered that he did not have a copy of the study and suggested I write

Firestone. After a number of calls and queries I received a two page

document from Firestone's Medical Director, E. Gates Morgan. The report

apears to be an in-house newsletter. (6) In it, a Mr. Ed Johnson is

interviewed about the Employer Assistance Program ("EAP") at Firestone.

There are some statements pertaining to absenteeism, but these are not

documented, and more importantly, refer only to a few alcoholics who have

been served by the Firestone EAP. The statistics generated (if these

calculations based on alcoholics were actually made) have nothing to do

with drug users, recreational or otherwise.

The statistics cited about absenteeism and workers' compensation

claims may have been derived from interviews with alcoholic workers

enrolled in the EAP at Firestone. These people were not identified by

urine testing for alcohol, but were referred because they or others

perceived that their lives were falling apart. They, unlike workers

randomly tested for drug use, were dysfunctional. To use them as a

justification for testing unimpaired workers is like demanding that all

workers have mandatory periodic rectal temperatures taken because a case

of

tuberculosis was found in the workplace.

III. THE RTI STUDY FOR DIMINISHED PRODUCTIVITY

The Research Triangle Institute ("RTI") of North Carolina issued

a

report in 1984 that attempted to calculate the economic cost to society

of

alcohol and drug abuse and mental illness. (7) It appears to be the

source of the claim that drug abuse costs the United States thirty-four

billion dollars a year in lost productivity. (8)

This claim seems to indicate that somehow individual worker

productivity was assessed by some quantitative measure and was noted to

be

seriously diminished. I often ask my students how they would design a

study which might quantify the effect of drug use or abuse on productivity

and they generate interesting ideas and designs. None, however, have ever

come up with anything as creative as the RTI report.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse ("NIDA") Household Survey

is

the actual source of the RTI statistics. (9) The RTI analysis itself does

not include any studies about productivity, dor does it document that drug

use was associated with any diminished productivity. The RTI report relied

on the 1982 version of the Household Survey, which included a question to

the adult (older than eighteen years of age) respondents about daily

marijuana use. If the respondent stated that he or she had ever used

marijuana daily for twenty or thirty days in one month, this respondent's

household income was compared to another household without a daily user.

The user households were estimated to have a household income approximately

twenty-eight percent less than those households that did not have such an

interviewee. According to the RTI report:

"These result have been used to calculate the reduced productivity

due to daily marijuana use. Once again, the prevalence rates of ever using

marijuana daily in the labor force by age and sex groups....were applied

to

the number of persons in the labor force from those groups that experienced

reducedproductivity. This number was multiplied by the expected

productivity in the workplace and in the household and then by the

impairment rate (27.9 percent) to produce the final value: The loss due

to

marijuana abuse was estimated at $34.2 billion for 1980." (10)

This somewhat opaque quotation means that the $34 billion "lost"

to

drug-induced diminished productivity and the one-third reduction is

productivity of the drug user come from a very unusual calculation. The

homes with daily users had a reduced household income. Because the daily

users all were between eighteen and thirty-four years of age, the

proportion of the work force represented by them was multiplied by total

income expected and this was multiplied by the reduction figure to generate

the $34 billion guess.

I have never seen a published analysis of the RTI study. It is a

complex and detailed document of one hundred thirty-seven pages whose

appendices number nearly one hundred thirty more. Although many of its

assumptions regarding the cost of alcohol and drug abuse are questionable,

I have focused only on the loss of productivity formulation.

The reduced income figure itself may be incorrect. It relies upon

reports from interviewees that they used drugs and relies upon their

estimates of household income. The income data were grouped in seven broad

categories with intervals as broad as $10,000. (11) To generate the

reduction figure with categories like this amounts to measuring centimeters

using a device graduated in meters.

The control households were generated by selecting a household

whose respondent resembled the marijuana use respondent. This meant that

the two respondents resembled each other in regard to age, education,

marital status, and occupation. (12) The similarities did not include

race, location, or nonchildren resident(s) in the household. Therefore,

a

twenty-four year-old single black, high school graduate brick-layer who

smokes marijuana and lives with his grandmother and uncle in Harlem, could

have his family income compared to a twenty-four year-old single white,

high school graduate, brick-layer living with his parents in an affluent

New Jersey suburb. If the household in Harlem had a lower income, it would

be attributed to diminished productivity caused by marijuana use.

As the RTI authors noted, however, the association between

marijuana use and reduced income is not necessarily causal. (13) Although

age and occupation were similar, the user may not have concerned himself

with income and may have made other job choices. (14) Moreover, the heavy

use of marijuana could have been secondary to job loss in a poor economy.

This manipulation, which assigned lost productivity to sometime

past heavy use of marijuana, did not show any association with current use

of marijuana (or any other drug), nor could it show any productivity

decrease due to past use of any other drug. It also could not show any

effect of any drug use in any person greater than age thirty-five. (15)

Thus, according to the study, regular use of marijuana in the past on the

part of females aged twenty-five to thirty-four cost the nation

$2,396,000,000. (16) However, marijuana use by females greater than

thirty-four, cost the nation nothing. (17) In males aged twenty to

twenty-four, regular marijuana use in the past would have cost the economy

$6,723,000,000. (18) On this basis, however, any use of cocaine,

prescription drugs, or phencyclidine (PCP) by this group cost the nation

nothing. Of course, the study really does not indicate this because its

inadequacy prevented any such calculations. Its inadequacy regarding the

marijuana calculations should be viewed in the same fashion. To stand in

front of an audience and say that drug use cost the nation $34 billion

dollars in decreased productivity is foolish and improper.

Readers may have noted that the past paragraphs followed the mode

of the RTI report and used income and productivity as equivalents. I do

not believe they are equivalents. Are those who choose to work in

positions where they earn less than the maximum possible less productive?

If so, a judge is less productive than a practicing lawyer, a medical

school professor is less productive than a practicing physician, a farmer

is less productive than a florist, and an elementary school teacher is less

productive than an owner of a day-care center.

IV. ILLEGAL DRUG USE IS DECLINING

In an affidavit filed in support of the federal government's

attempt to promote urine testing of certain federal employees under the

President's executive order, J. Michael Walsh characterized the drug

problems in America as pervasive:

"Overall, 70.4 million Americans age 12 and over 37% of the

population have used marijuana, cocaine or other illicit drugs at least

once in their lifetime. Nineteen percent of the population age 12 and over

36.8 million have used illicit drugs at least once in the past year, and

12

% at least once during the month prior to being surveyed." (19)

Walsh himself later notes that of the 70.4 million Americans who have tried

an illicit drug at least once in their lives, for most (sixty two million)

that drug was marijuana. (20)

Many of the proponents of testing use such data. Proponents,

however, do not often seem to notice that this same data reveals that

almost fifty percent of those who have ever used an illegal drug at least

once have not used an illegal drug in the past year and perhaps never will

again. (21)

The sources of these data are important and interesting and merit

careful attention. There are two important surveys funded by the National

Institute on Drug Abuse from which most of our knowledge about the use of

illegal drugs in the United States is derived. These surveys are the

National Household Survey and the annual High School Senior Survey. (22)

Both surveys, however, were not constructed to signal serious heavy drug

use:

"The unique contribution of serveys of the general population lies

in their ability to furnish prevalence estimates that include many forms

of

drug use that never come to the attention of medical and legal

authorities.....Survey responses permit classification of drug-using

behavior along a continuum of involvement, substituting empirical for

arbitrary definitions of medically or socially pathologic conditions, and

emphasizing the typical nature of the phenomenon rather than its most

dramatic manifestations." (23)

These words from the forward to the National Household Survey published

in

1983 seem particularly calm in the light of the frequent repetition of its

glaring numbers to induce employers and others to join in the zealot's

game.

The National Household Survey is a general population survey of

household members aged twelve and above and has been conducted every two

to

three years since 1971. It excludes individuals in institutionalized

settings (colleges, prisons, military bases) and, therefore, as

conservative. Because each respondent gives general data, it can monitor

trends by age and sex and other demographic variables.

The annual High School Senior Survey obtains self-reported

information from approximately 130 high schools in the continental United

States. Between 16,000 and 18,000 seniors are surveyed. In addition, the

investigators construct a sub sample of individuals from each class who

are

followed, yielding a longitudinal study.

These two surveys do not yield a horrible story of an American

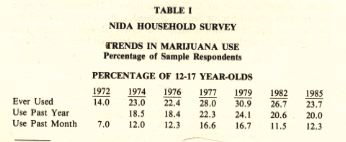

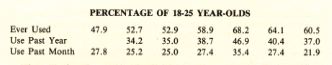

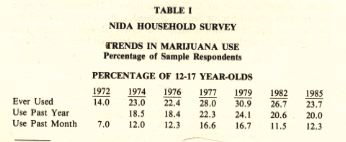

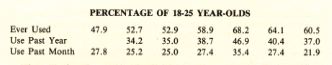

decline into profligate drug use, but exactly the opposite. Table I

depicts data from the Household Survey regarding marijuana use over time.

(24) Since 1979, the data indicate a significant decline in use among the

two important youth groups. In the eighteen to twenty-five group, the

percentage of the population that had ever used marijuana declined from

68.2% to 60.5% Those who had used marijuana in the year preceding the

survey declined from 46.9% to 37% and in the last month preceding the

survey, from 35.4% to 21.9%.

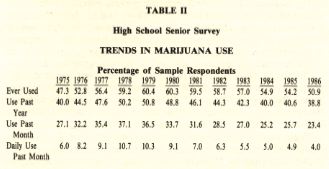

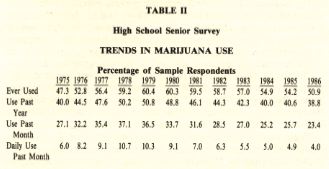

These national trends also are reflected in the High School Senior

Survey (Table II). (25) The apex of marijuana use in this group also was

noted in 1979 and has steadily declined. Marijuana use in the month

preceeding the survey fell from 33.7% to 23.4%. Daily use has steadily

declined from 10.3% to 4.0%

During the growing clamor to test working Americans, interest in

marijuana, the most widely-accepted illegal drug, has declined, and

declined significantly. This fact is not stressed by those frequently

quoting the two survey instruments.

The use of cocaine shows a different but still hopeful pattern.

Between 1974 and 1985, the lifetime prevalence of cocaine use increased

from 5.4 million users to 22.2 million users. (26) However, the trend in

the High School Senior Survy showed a distinct leveling off between 1982

and 1985 with a slight decrease. (27) In 1987, cocaine use by high school

students and young adults dropped twenty percent. (28) Again, a quarter

of

those reporting cocaine use had not used the drug in the last year. The

decline noted for marijuana has occurred in most drug categories in the

High School Survey including a decline in current and daily use of alcohol.

(29)

V. INDUSTRIAL ACCIDENTS AND RAILROAD EMPLOYEES

Among the fears fueling the drive to test is the specter of

industrial accidents and the likelihood of intoxicated workers harming

other workers and the public. The lack of data that drug use in industry

is harmful or an important cause of accidents does not deter the frequent

attribution of accidents to drug use.

Nowhere is this discussion more focused than on transportation. It

is impossible to raise arguments about testing without provoking commentary

on intoxicated airplane pilots and locomotive engineers. Perhaps the

strongest impetus to testing occurred on January 4, 1987, when a Conrail

engineer, who later tested positive for marijuana, ignored a number of

warning devices and pulled his train into the path of an Amtrak Metroliner.

(30) Sixteen people were killed. (31)

From February 10, 1986 to January 15, 1987, under the auspices of

the Federal Railroad Administration ("FRA"), most American rail

carriers

conducted an incident-based testing program. Any train accident or

incident associated with a fatality, injury, or nontrivial property damage

resulted in the testing of all operating personnel--- including the train

crews, dispatcher, and policemen. One hundred seventy-five events in the

year led to the testing of 759 employees. (32) Of the 759 employees

sampled, 43 tested positive for controlled substances including alcohol.

(33) Of the forty-three positives, the drugs identified were as follows:

Alcohol = 9 (1.2%)

Illicit drugs = 29 (3.8%)

Other controlled substances = 14 (1.8%).

(34)

The FRA made public the specific results only for the alcohol and

illicit drug positives, so it was not possible to know which licit drugs

(one assumes obtained by prescription) were identified in the fourteen

workers. Of the twenty-nine (3.8%)positives for illicit drugs, eighteen

had only THC carboxylic acid (marijuana metabolite). five had only

benzoylecgonine (cocaine metabolite) and six had both. (35) One

individual who tested positive for methamphetamine also had tested positive

for marijuana and is included in the eighteen. Despite its listing as

illicit, methamphetamine is still available in the United States as a licit

appetite depressant.

The FRA document correctly noted that these "data are not

conclusive of alcohol/drug role in industrial accidents." (36) Indeed,

of

the twenty-nine, at least seven had job classifications which would seem

to

place them at a distance from operating decisions (track patrolman, ticket

taker, conductor, road master). (37)

This costly program is not cited for what appears to be significant

evidence that illicit drugs do not play an obvious role in industrial rail

accidents. Furthermore, there is no reason to believe that an

investigation of other industrial accidents would yield a different

picture.

VI. MARIJUANA ISSUES

Because most workplace positives are due to marijuana metabolite

and most arguments revolve around the putative dangers of off-the-job

marijuana use, the details of cannabinoid testing are important. A review

of these details is, however, beyond the scope of this article. (38)

However, three points involving marijuana that are commonly used to provoke

testingt merit some discussion. First, the fat storage and carry-over

effect of marijuana. Second, the airplane simuator testing study.

Finally, the growing potency of domestically available marijuana.

A. Fat Storage and Effect

The persistence and storage of THC and other cannainoids after use

is subject to much discussion and misunderstanding. Figure 1 depicts the

length of time THC remains in the plasma after an individual smokes

marijuana containing delta-9-THC (the intoxicating ingredient in

marijuana). (39) The pattern of distribution follows, with some

simplification, what pharmacologists refer to as a two-compartment model.

The drug initially enters the blood stream (compartment I) and then is

rapidly distributed to the deep compartment II, which is most of the body.

The initial rapidly declining concentration curve represents the

disappearance from the blood stream through distribution.

Three to four hours after the initial ingestion, the concentration

of delta-9-THC has fallen below 2-5 ng. ml in the blood. (40) This

concentration represents the minimal effective concentration. (41) Below

this concentration in the blood, the drug exerts no demonstrable effect.

We assume that like other drugs, the concentration has fallen so that the

complementary concentration in the brain and other receptor tissue is below

the threshold which will produce an effect. However, delta-9-THC remains

in the body.

The second phase of the disapearance curve is nearly level because

its decline is so gradual. This phase represents to some degree the drug's

redistribution from compartment II to compartment I. This slow decline is

used to calculate the terminal half-life (T 1/2) of THC. A low

concentration, say 1.0 ng ml, will take more than twenty-four hours to fall

to .05 ng / ml. (42) Actually, it probably takes even more time, but an

accurate calculation is difficult because of the inability to measure

extremely low concentrations.

This slow decline is the source of the popularly-held concept that

THC persists in the body's fat. From this another speculation usually

follows. The speculation is that the THC still is exerting some effect.

Current evidence simply says this is not so. There are many speculations

about the long-lasting effects of THC, but in the nearly thirty years since

delta-9-THC was discovered, nothing has been verified. The brain actually

contains little fat and there is no evidence to support the idea that the

drug particularly persists there. Frequent users will carry the drug and

its metabolites with them--even to the workplace--but they also will carry

some amount of organochlorine pesticide, lead, and the hydrocarbon solvent

used at work. We might better and more profitably examine the long term

effects of these substances.

B. Airplane Simulator Testing In Private Pilots

To justify the intrusion of testing, studies purporting to show a

lasting effect of marijuana have been widely cited. Marijuana users and

their defenders frequently state that marijuana use-off-the-job is no

different than alcohol use off-the -job.

The effects of marijuana and the selective impairment generated by

its use dissipate within three to four hours and generally correlate with

the decline in serum tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) to levels of less than 5

ng / ml. (43) The studies of Herbert Moskowitz and Robert Petersen that

indicate impairment of some psychomotor function for up to eight hours

(44) are puzzling and not entirely scientifically acceptable. However,

assuming they are correct, they still do not indicate that off-the-job drug

use causes on-the-job impairment. A study by Dr. Jerome Yesavage is

another matter. (45) This study using flight simulators has been widely

discussed and previously used as a strategic justification for urine

testing. (46) The study identifies significant impairment twenty-four

hours after smoking marijuana in a group of volunteer pilots who performed

on a flight simulator. (47) These conclusions are striking and have not

yet been replicated or confirmed.

After careful analysis of the article, I think that the

experimental methodology was so flawed that the study does not prove

impairment at twenty-four hours. (48) Briefly, the study was uncontrolled

and, therefore, scientifically unreliable. The subjects were studied with

no placebos or attempts to conceal the active treatment. Subject efforts

at a control run were compared to their efforts after they, and the

investigators, knew that they had consumed an active drug. This violates

elementary rules of study design and constitutes a serious flaw in the

study. The study also fails to deal with the characteristics and prior

drug experience of the volunteers, the issues of repeated testing and

training upon the simulator, and the generation of a large number of

simulator-generated measures some of which may have varied by chance. (49)

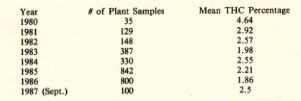

C. THC Content (Potency) of Domestically Available Marijuana

A commonly stated and widely accepted belief is that marijuana's

past record of causing minimal harm to users was based on the use of

low-grade material. Many plants, particularly those growing wild, have a

low content of delta-9-THC. (50) It is often stated that the THC content

has increased greatly. In fact, critics and proponents of testing sound

like dealers extolling the power of Hawaiian and California grown material.

"A glance at the percentages of THC in confiscated marijuana

would....[indicate] that marijuana is now as strong as hashish in THC

content," (51)

This particular claim also has been difficult to document.

However, NIDA has funded a THC analysis program at the University of

Mississippi since 1980. Under the program, the University analyzes plants

received chiefly by law enforcement agents, both federal (Drug Enforcement

Agency) and a variety of city and state criminal agencies. The

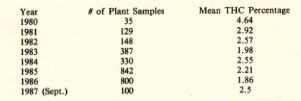

accompanying table lists the findings since 1980. (52)

The sampling is irregular but chiefly reflects material seized by

these agencies from the back yards, frms, and even indoor hydroponic

systems of growers. The most suspect year, 1980, of course, is the only

one in which the mean percentage exceeded three percent. There has been

no

real change and certainly no real increase in marijuana potency in the

1980's.

Interestingly, significant variation in THC content of marijuana

does not necessarily result in greater delivery. In a study of the

delivery of THC into smoke under standard conditions, 16-19% of the THC

content of a cigarette actually appeared in the smoke. (53) Increasing

the THC content under some circumstances did not influence delivery. For

example, cigarettes carefully prepared to contain 1.6% THC and 3.1% THC

delivered the same amount of THC in smoke. (54)

VII. CONCLUSIONS

This article has examined a series of rationales for the imposition

of urine testing onto unimpaired American workers. I have tried in good

faith to examine the arguments from the perspective of empirical studies

and appropriate analysis. I have accused, not subtly, the proponents of

testing of zealotry and improper use of statistics and data to support a

moral stance. To some degree my bias as a civil libertarian has affected

my evaluation. In the long run, however, the truth about this conflict

will depend upon ideas and data and not biography. Urine testing is a

wrong-headed intervention into the lives of some by those with power over

them. It is not a search for illness but a search for deviance conducted

in an un-American manner. Drug abuse is a specter of the 1980's resembling

the specter of domestic communism of the 1950's. Under the guise of

helping, the proponents of testing are creating enormous harm. Urine

testing is simply drug abuse abuse.

FOOTNOTES

1 Angarola & Brunton, "Substance Abuse in the Workplace: Legal

Implications for Corporate Actions," in SUBSTANCE ABUSE IN THE WORKPLACE

35-36 (1984) (hereinafter Angarola & Brunton).

2 id. at 36.

3 "Proficiency Standards for Drug Testing Laboratories: Hearings Before

a

Subcomm. of the House Comm. on Government Operations, 100th Cong., 1stt

Sess. 91-92 (1987) (statement of Mark de Bernardo, Special Counsel for

Domestic Policy and Manager of Labor Law. U.S. Chamber of Commerce)

[hereinafter Statement of de Bernardo].

4 See Angarola & Brunton, supra note 1, at 35.

5 Cohen, "Drugs in the Workplace," 12 DRUG ABUSE & ALCOHOLISM

NEWSL. I.

I (Aug. 1983).

6 Photocopy sent from E. Gates Morgan to Dr. John Morgan (Nov. 1986)

(discussing Firestone "Study") (copy on file at the Kansas Law

Review).

7. RESEARCH TRIANGLE INSTITUTE, ECONOMIC COSTS TO SOCIETY OF ALCOHOL AND

DRUG ABUSE AND MENTAL ILLNESS: 1980 (1984) [hereinafter RTI STUDY].

8. See Statement of de Bernardo, supra note 3, at 89. "$60 billion

is the

annual cost to the business community for drug abuse, a 30 percent increase

in only three years. One half of that cost is in lost productivity."

Id.

(emphasis in original). de Bernardo did not cite any source for this

statement. See also Church, "Thinking the Unthinkable," TIMEm

May 3,

1988, at 14 (chart).

9. See RTI STUDY, supra note 7, at 67-68 (citing NATIONAL INSTITUTE ON

DRUG ABUSE HIGHLIGHTS OF THE 1982 HOUSEHOLD SURVEY ON DRUG ABUSE (1983)

[hereinafter 1982 NATIONAL HOUSEHOLD SURVEY].

10. RTI STUDY, supra note 7, at A-22. Interestingly, the data relied upon

showed that adults thirty-five and older effectively had a zero prevalence

rate of ever using marijuana on a daily basis. Id. at A-20.

11. Id. at A-20.

12. Id. at A-9.

13. See id. at A-24.

14. Id.

15. See supra note 10.

16. See RTI STUDY, supra note 7, at 68.

17. Id.

18. Id.

19. Declaration of J. Michael Walsh, Ph.D., Director of Workplace

Initiatives, National Institute on Drug Abuse, at 2, submitted with

Department of Justice Memorandum of Support for Summary Judgment, American

Fed'n of Gov't Employees, Civ.No. 87-1797, 87-2350 (D.D.C. March 1, 1988)

[hereinafter Declaration of J. Michael Walsh, Ph.D.].

21. id.

22. NATIONAL HOUSEHOLD SURVEY, supra note 9; NATIONAL INSTITUTE ON DRUG

ABUSE US DEPT OF HEALTHE AND HUMAN SERVICES, NATIONAL TRENDS IN DRUG USE

AND RELATED FACTORS AMONG AMERICAN HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS AND YOUNG ADULTS,

1975-1986 [hereinafter HIGH SCHOOL SENIOR SURVEY].

23. 1982 NATIONAL HOUSEHOLD SURVEY, supra note 9, at 1.

24. Kozel & Adams, "Epidemiology of Drug Abuse: An Overview,"

234

SCIENCE 970, (1986) [hereinafter Kozel & Adams] (citing NATIONAL

INSTITUTE ON DRUG ABUSE, HIGHLIGHT OF THE 1985 HOUSEHOLD SURVEY ON DRUG

ABUSE (Nov. 1986).

25. HIGH SCHOOL SENIOR SURVEY, supra note 22, at 47-50.

26. Kozel & Adams, supra note 24, at 973.

27. HIGH SCHOOL SENIOR SURVEY, supra note 22, at 47-50

28. Statement by Dr. Lloyd D. Johnstone, U.S. Dept. of Health and Human

Services News Conference (Jan. 13, 1988) (copy on file at the KANSAS LAW

REVIEW). Dr. Johnston is one of the principal authors of the High School

Senior Survey.

29. Id.

30. Se N.Y. Times, Jan. 5, 1987, at 1, col. 2.

31. Id.

32. Federal Railroad Administration, U.S. Dep't of Transp., Summary of

Post-Accident Testing Events Feb. 10, 1986 through Jan. 15, 1987

(summarized in 53 Fed. Reg. 46,641 (summary includes data through Dec. 31

1987).

33. Id.

34. Id.

35. Id.

36. Id.

37. Id.

38. See generally Morgan, "Marijuana Metabolism in the Context of Urine

Testing for Cannabinoid Metabolite, 20 J. PSYCHOACTIVE DRUGS 107 (1988).

[Editor's Note: See Miike & Hewitt, "Accuracy and Reliability of

Urine

Drug Tests. 36 KAN. L. REV. 641 (1988).

39. Id. at 109 (reprinted with permission).

40. Augerell, Lindgren, Ohlsson, Gillespie, & Hollister, "Recent

Studies

on the Pharmacokinetics of Delta-1-Tetrahydrocannabinol in Man," in

THE

CANNABINOIDS: CHEMICAL, PHARMACOLOGIC, AND THERAPEUTIC ASPECTS 167

(1984).

41. See id. at 179.

42. Cf. E. Johansson, Prolonged Elimination Half-life in Plasma of

delta-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol in Chronic Marihuana Users 41 (abstract of

presentation given Sept 4, 1987 ( copy on file at the Kansas Law Review).

43. See supra notes 40-42 and accompanying test.

44. H. Moskowitz & R. Petersen, MARIJUANA AND DRIVING -- A REVIEW

(1980).

45. Yesavage, Leirer, Denari & Hollister, "Carry-Over Effects of

Marijuana Intoxication on Aircraft Pilot Performance: A Preliminary

Report," 142 AM. J. PSYCHIATRY 1325 (1985) [hereinafter Yesavage].

46. See, e.g., Declaration of Dr. Marian W. Fischman Associate Professor,

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Johns Hopkins University

School of Medicine, at 2, submitted with Department of Justice Memorandum

of Law in Support of Motion for Summary Judgment, American Fed'n of Gov't

Employees v. Dole, Civ. No. 87-1815 GAG (D.D.C. Sept. 30, 1987);

Declaration of J. Michael Walsh, Ph.D., supra note 19, at 6.

47. Yesavage, supra note 45, at 1328.

48. See Morgan, "Carry-Over Effects of Marijuana," 144 AM. J.

PSYCHIATRY

259, 259-60 (1987) (letter to the editor); see also Greenblatt,

"Marijuana Test Fails in Scientific Design," N.Y. Times, Apr.

30, 1986 at

A-30 col. 4 (letter to the editor).

49. Whenever one measures many variables using a five percent level of

significance, one in twenty will vary by chance.

50. See Mikurya & Aldrich, "Cannabis 1988 Old Drug, New Dangers,

The

Potency Question," 20 J. PSYCHOACTIVE DRUGS 47, 52 (1988).

51. S. Cohen, THE SUBSTANCE ABUSE PROBLEMS,VOLUME TWO, NEW ISSUES FOR THE

1980's 65 (1985) (citing NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL, AN ANALYSIS OF

MARIJUANA POLICY (1982).

52. Telephone interview with Carol Abel, University of Mississippi

Research Institute (Feb. 4, 1988).

53. Davis, McDaniel, Cadwell & Moody, "Some Smoking Characteristics

of

Marijuana Cigarettes," in THE CANNABINOIDS: CHEMICAL, PHARMACOLOGIC,

AND

THERAPEUTIC ASPECTS 102 (1984).

54. Id.

INDEX

HOME